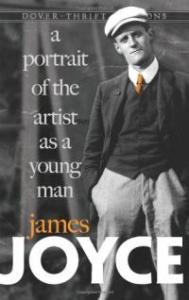

For too many years, I was afraid to read James Joyce. Most of this fear was based on what I had read about the novel, Ulysses. Opinions of his book ran the gamut from, this:

“One of the books that caused great harm was James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is pure style. There is nothing there. Stripped down, Ulysses is a twit.”

– Paulo Coelho

to the more informed, this:

(from a column addressing Coelho’s opinion): “…Only someone who had barely glanced at Ulysses would damn it for “pure style”…

…Whenever there is a reactionary attack on contemporary literature, a snipe at Joyce is necessary…The real slander is to the reader, or rather, to readers. Note how the anti-Joyceans have all read him and then tell readers he’s not for them: too difficult, too abstruse, too weird – with the “for you” hanging in the background. I’ve been there, they say, and you wouldn’t like it. It is an attitude that surreptitiously belittles the reader. There is nothing as profoundly patronising as a middlebrow, supposedly “literary” author on a soapbox.”

Maybe Ulysses can’t be summarised into a sentence-long quote such as: “Remember that wherever your heart is, there you will find treasure.” Perhaps life is actually a bit less pat than that.”

– Stuart Kelly, The Guardian

You have to take a course just to understand Joyce, I was once forewarned, a long time ago.

However, I am pleased to say I chipped away a little at my fear of reading Joyce as I read “Salinger and Sobs,” part of an essay collection called Loitering. In this essay, writer Charles D’Ambrosio makes reference to Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist… and how he came to read the novel:

“…I read Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man strictly for its creepy Jesuit milieu and the way Stephen Dedalus uses difference and snobbery to escape. The reading of Portrait was itself a Dedalean act of snobbery on my part, a pose I hoped would piss off the jocks at my Jesuit boys school.”

Stephen Dedalus, the protagonist of Joyce’s Portrait, a coming of age novel derived from his own life, also attended a Jesuit school. A disturbing passage from Portrait describes 10 year old Dedalus as he is unmercifully whacked with a pandy bat by the Jesuit prefect of studies under false pretenses:

Check out the size of this instrument of torture

“Stephen closed his eyes and held out in the air his trembling hand with the palm upwards. He felt the prefect of studies touch it for a moment at the fingers to straighten it and then the swish of the sleeve of the soutane as the pandybat was lifted to strike. A hot burning stinging tingling blow like the loud crack of a broken stick made his trembling hand crumple together like a leaf in the fire: and at the sound and the pain scalding tears were driven into his eyes.”

As it happens, in the days when corporal punishment was condoned in public schools, I had a 6th grade teacher who owned a pandy bat, which he kept in his desk draw. This teacher was an old-school, died-in-the-wool Catholic and, no doubt, a product of a Jesuit education. Because why would he own a pandy bat?

The good ole days

It didn’t take much to provoke this teacher to whip out the bat. Once in hand, he proceeded to inflict great pain, just as Joyce describes above. Talking in class or not paying attention or worse would determine the amount of whacks delivered — but, only to the boys in the class.

Girls, on the other hand, were never whacked. Instead, he would shoot the offending girl a piercing, cold stare while tapping, in steady intervals, the eraser of his Dixon-Ticonderoga yellow pencil on his desk until the girl looked up and their eyes met. It was terrifying (I was once on the receiving end of his murderous stare — I was a talker). But not nearly as bad as what the boys had to endure — and suck up.

I related to much of what Joyce writes about in this book, having grown up quasi-Catholic. As the child of an agnostic mother and lapsed-Catholic father, I, nevertheless, attended religious instruction until I was 15 years old, participated in all the required sacraments, until I found the courage to confront my parents and stage my own revolt.

That said, it is Joyce’s glorious writing, the story, his beautiful turn of phrase, command of the vernacular, erudition and sharp dialogue that captivated me from beginning to end. Stephen’s sweetness as a child; his earnestness to be good and not to sin is heartbreaking; and becomes even more so as he reaches adolescence, when he is still trying to fit in and find his place in the world while battling hormones and torturous Catholic guilt.

The ending of the novel holds within it the thrilling promise of liberation — something Stephen Dedalus has yearned for throughout. The reader rejoices for Stephen; and also identifies with him — while, at the same time, worries for him. The world can be an unforgiving place.

Finishing this great novel prompted me to read up on the novel, Ulysses. The book is brilliantly structured. It takes place in the course of a single day (June 16, 1904 — James Joyce would have been 22 years old in 1904); and each chapter is devoted to a single hour in that day. The story is based on Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey — and, delightfully, I learned that Stephen Dedalus reappears in the novel as the character, Telemachus.

“Only when we are no longer afraid do we begin to live.”

– Dorothy Thompson

I am no longer afraid of reading James Joyce. Bring on Ulysses.